New

research from the Niels Bohr Institute at the University of Copenhagen

has shown that the rise in temperature after the last ice age into the

warmer intergrlacial period was followed closely by a rise in

atmospheric carbon dioxide, contrary to previously held opinion.

The research was published in the journal Climate of the Past and showed that, unlike what previous thought had shown, the increase in the amount of CO2 in the atmosphere following the end of the last ice age, approximately 19,000 years ago, followed a lot closer to the rise in temperature.

“Our analyses of ice cores from the ice sheet in Antarctica shows that the concentration of CO2 in the atmosphere follows the rise in Antarctic temperatures very closely and is staggered by a few hundred years at most,” explains Sune Olander Rasmussen, Associate Professor and centre coordinator at the Centre for Ice and Climate at the Niels Bohr Institute at the University of Copenhagen.

The research was based on measurements of ice cores taken from five boreholes through the Antarctic ice sheet.

“The ice cores show a nearly synchronous relationship between the temperature in Antarctica and the atmospheric content of CO2, and this suggests that it is the processes in the deep-sea around Antarctica that play an important role in the CO2increase,” explains Sune Olander Rasmussen.

Rasmussen explained that one of the theories is that when Antarctica warms there will be stronger winds over the Southern Ocean, which will force more water up from the deep bottom layers of the ocean where there is a much higher concentration of carbon dioxide. As this happens, a larger percentage of carbon dioxide will be released into the atmosphere, linking temperature and CO2 together.

The collapse of the last ice age is linked to the change in solar radiation caused by variations in the Earth’s orbit around the sun, the Earth’s tilt, and the orientation of the Earth’s axis. These variations are called Milankowitch cycles and take place in cycles of approximately 100,000, 42,000, and 22,000 years. These are the cycles that cause the Earth’s climate to shift between long ice ages of approximately 100,000 years and warm interglacial periods, typically 10,000 – 15,000 years.

“What we are observing in the present day is the mankind has caused the CO2content in the atmosphere to rise as much in just 150 years as it rose over 8,000 years during the transition from the last ice age to the current interglacial period and that can bring the Earth’s climate out of balance,” explains Sune Olander Rasmussen adding “That is why it is even more important that we have a good grip on which processes caused the climate of the past to change, because the same processes may operate in addition to the anthropogenic changes we see today. In this way the climate of the past helps us to understand how the various parts of the climate systems interact and what we can expect in the future.”

Source: University of Copenhagen

Planetsave (http://s.tt/1j2JT)

Planetsave (http://s.tt/1j2JT)

The research was published in the journal Climate of the Past and showed that, unlike what previous thought had shown, the increase in the amount of CO2 in the atmosphere following the end of the last ice age, approximately 19,000 years ago, followed a lot closer to the rise in temperature.

“Our analyses of ice cores from the ice sheet in Antarctica shows that the concentration of CO2 in the atmosphere follows the rise in Antarctic temperatures very closely and is staggered by a few hundred years at most,” explains Sune Olander Rasmussen, Associate Professor and centre coordinator at the Centre for Ice and Climate at the Niels Bohr Institute at the University of Copenhagen.

The research was based on measurements of ice cores taken from five boreholes through the Antarctic ice sheet.

“The ice cores show a nearly synchronous relationship between the temperature in Antarctica and the atmospheric content of CO2, and this suggests that it is the processes in the deep-sea around Antarctica that play an important role in the CO2increase,” explains Sune Olander Rasmussen.

Rasmussen explained that one of the theories is that when Antarctica warms there will be stronger winds over the Southern Ocean, which will force more water up from the deep bottom layers of the ocean where there is a much higher concentration of carbon dioxide. As this happens, a larger percentage of carbon dioxide will be released into the atmosphere, linking temperature and CO2 together.

The collapse of the last ice age is linked to the change in solar radiation caused by variations in the Earth’s orbit around the sun, the Earth’s tilt, and the orientation of the Earth’s axis. These variations are called Milankowitch cycles and take place in cycles of approximately 100,000, 42,000, and 22,000 years. These are the cycles that cause the Earth’s climate to shift between long ice ages of approximately 100,000 years and warm interglacial periods, typically 10,000 – 15,000 years.

“What we are observing in the present day is the mankind has caused the CO2content in the atmosphere to rise as much in just 150 years as it rose over 8,000 years during the transition from the last ice age to the current interglacial period and that can bring the Earth’s climate out of balance,” explains Sune Olander Rasmussen adding “That is why it is even more important that we have a good grip on which processes caused the climate of the past to change, because the same processes may operate in addition to the anthropogenic changes we see today. In this way the climate of the past helps us to understand how the various parts of the climate systems interact and what we can expect in the future.”

Source: University of Copenhagen

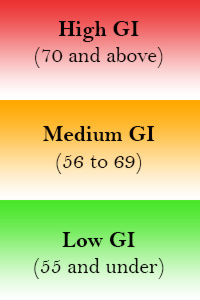

This

is important information – not only for diabetics but also for those

interested in losing weight – because foods high on the glycemic index

scale tend to give you a "sugar rush." They cause insulin to be released

into your bloodstream to process the sudden rise in blood sugar.

Unfortunately, once the blood sugar levels have been normalized, your

body then has a tendency to crave more food to boost them again, causing

a kind of "yo-yo" approach to eating. Also, insulin is considered a

"fat storage hormone" because it causes sugar to enter the body's cells

more quickly, so that it can be converted to energy, but at the same

time causes them to store the excess sugars as glycogen or body fat.

This

is important information – not only for diabetics but also for those

interested in losing weight – because foods high on the glycemic index

scale tend to give you a "sugar rush." They cause insulin to be released

into your bloodstream to process the sudden rise in blood sugar.

Unfortunately, once the blood sugar levels have been normalized, your

body then has a tendency to crave more food to boost them again, causing

a kind of "yo-yo" approach to eating. Also, insulin is considered a

"fat storage hormone" because it causes sugar to enter the body's cells

more quickly, so that it can be converted to energy, but at the same

time causes them to store the excess sugars as glycogen or body fat.